The theme of Saint George and the dragon has captivated artists throughout history, from Giotto and Raphael to Paolo Uccello and Salvador Dali.

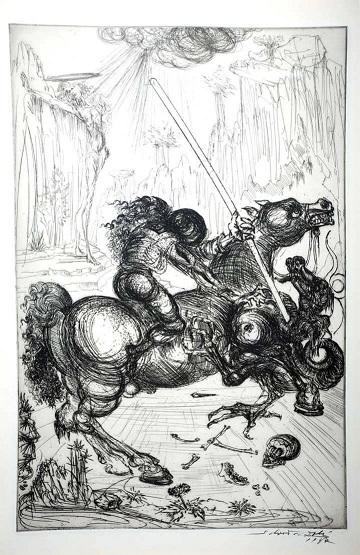

The Catalan artist explored this subject in various media, including his 1942 painting “Saint George” and the 1947 etching “Saint George and the Dragon” (which shows Raphael’s influence).

His bronze sculpture, “Saint George and the Dragon,” offers a symbolic reinterpretation of the traditional iconography, depicting the halo-less saint, a gallant knight in shining armor, at the moment of triumph over evil, delivering the fatal blow to the dragon and freeing the princess.

The sculptural “Saint George and the Dragon” shares several similarities with Raphael’s circa 1505 painting of the same name, housed in the Louvre. Dalí, during his time in Paris, meticulously studied Raphael’s works, considering him “the very genius of the Renaissance.” In his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, he proclaimed, “If I look toward the past, beings like Raphael appear to me as true gods; I am perhaps the only one today to know why it twill henceforth be impossible even remotely to approximate the splendors of Raphaelesque forms.”

Both works portray Saint George on horseback, clad in shining armor, about to slay the dragon. Raphael’s saint with a sword, Salvador Dali’s with a lance. The compositions are diagonally oriented, with the rearing horses and spiraling, upward-pointing dragon tails and wings enhancing the dynamism. Dalí’s piece uses compositional balance and ideal diagonals to emphasize the duality of good and evil. The saint’s lance creates a diagonal from the dragon’s head to the knight’s arm and, ideally, to the princess. The dragon’s wings form an opposing diagonal, reinforcing once again Dalí’s focus on perspective, mathematics, aesthetics, and composition.

The artwork and Dalí´s readings

The sculpture is rich in symbolism and metamorphosis. Saint George and the princess’s faces are devoid of detail, the dragon’s wings morph into flames, and its tongue becomes a crutch, a recurring Dalinian symbol. The artist represents the duality of life and death, good and evil. The horse’s expression, seemingly unafraid of the dragon’s fiery wings, draws energy and awareness from them, transmitting this to the knight in perfect compositional harmony. The warhorse actively participates in the struggle, emboldening Saint George to overcome his fears, defeat the dragon, and conquer human obsessions and temptations. Only through the dragon’s symbolic death can balance and new life be achieved. “Death and resurrection, revolution and renaissance – these are the Dalinian myths of my tradition,” Dalí stated.

The crutch, a “symbol of death and the symbol of resurrection” for Dalí, first struck him as “untoward and prodigiously striking […] The superb crutch! Already it appeared to me as the object possessing the height of authority and solemnity”. In the sculpture, the dragon’s forked tongue, the lance, and the knight’s attire are shiny. For Dalí, “Glory is a shiny, pointed, cutting thing, like an open pair of scissors.”

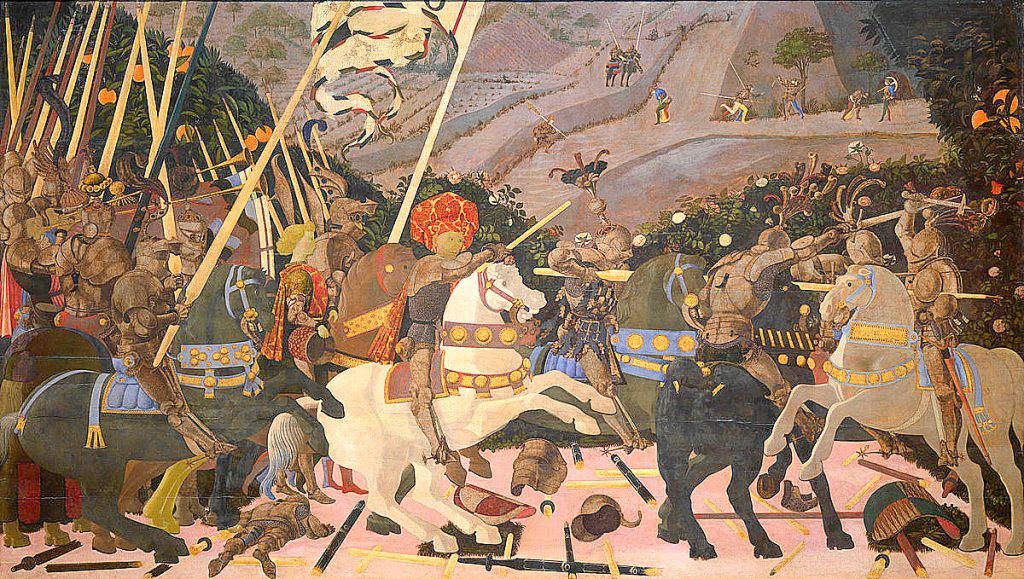

The dragon’s head and open mouth recall Paolo Uccello’s “Saint George and the Dragon” (c. 1460), while the horse’s rearing posture is influenced by other Uccello’s works, particularly “The Battle of San Romano” and by the horses of Leonardo da Vinci. Dalí studied Leonardo’s horse anatomy and admired Uccello’s “grace and mystery” in depicting his subjects.

Another symbolic detail is the dragon’s fish-like skin and numerous scales. Dalí’s obsession with fish is documented in his Diary of a Genius, where he recounts an episode of using “glittering scales of my flying fish” to add sheen to a canvas, attracting flies and leading him to exclaim, “My God, I’m turning into a fish! […] I was covered with shimmering scales!”

Saint George and Salvador Dali re-connection with faith

Since 1995, a museum-sized version of “Saint George and the Dragon” resides in the Vatican Museums, a gift from the Dalí Universe to Pope John Paul II. It is now located near the Stairway of Pius IX.

The sculpture illuminates Dalí’s relationship with faith. “While waiting for the faith that is the grace of God, I have become a hero,” he said. His childhood was marked by conflicted feelings towards Catholicism, with his devoutly Catholic mother and atheist father. His first teacher reinforced the idea that “religion was a woman’s business.” Nietzsche, along with his mother’s example, sparked his mystical questions, culminating in his 1951 “Mystic Manifesto.” “Nietzsche awoke in me the idea of God,” he wrote.

Dalí sought to incorporate mystic and religious themes into Surrealism, proposing a new religion that was “at once sadistic, masochistic, and paranoiac.” He proclaimed, “I admit that at that period I already anticipated that we would return to the truth of the Apostolic Roman Catholic religion, which was slowly beginning to overwhelm me with its glory.” Later, he declared, “I am surrealism…And I believe it, because I am the only one who is carrying it on. I have repudiated nothing; on the contrary, I have reaffirmed, sublimated, hierarchised, rationalised, dematerialised, spiritualised everything. My present nuclear mysticism is merely the fruit, inspired by the Holy Ghost, of the demoniacal and Surrealist experiment of the first part of my life.”

Dalí spent his life searching for faith, for heaven, which he defined as “neither above nor below, neither to the right nor to the left, heaven is to be found exactly in the center of the bosom of the man who has faith.” Salvador Dali´s “Saint George and the Dragon,” filled with symbolic references and hidden meanings, holds a significant place in his oeuvre, exploring the dualities of good and evil, life and death, earth and heaven.

Where can you see it?

The bronze “Saint George and the Dragon” is an authentic Salvador Dali limited edition that we proudly have in our collection. If you are curious to see it, drop us a line. We´ll be happy to direct you to the nearest exhibition showcasing ours or another from this edition.